CEO’s Corner: Justice by Design- What a Tech-Based Movement Looks Like

Dear Partners in Progress,

Dear Partners in Progress,

We are witnessing a revolution— and it’s not being televised. It’s being coded. It’s being recorded. It’s being organized by everyday people refusing to be silenced by systems that have historically treated them as disposable.

At Lustitia Aequalis, we’re not just imagining a fairer world, we’re building the tools to demand it. We believe justice must be accessible, actionable, and accountable. That’s why we’re at the forefront of a civic tech movement reshaping what equality and empowerment looks like in real time for your civil and human rights with law enforcement and medical centers across the globe.

Our focus is bold and unflinching: protecting your rights at the intersection of law enforcement and healthcare.

💡 When Injustice Shows Up in a Lab Coat or a Badge

We refuse to accept that being sick or scared should make you a suspect. Too often, the systems designed to care, protect, and serve become the ones that criminalize us—especially if you’re Black, Brown, undocumented, poor, homeless, 0or struggling with mental health. Whether it’s a police stop gone wrong or a hospital visit that ends in handcuffs, we are fighting back with tools, knowledge, and truth.

From our Witness app that helps people safely record encounters, to our rights literacy campaigns teaching communities what to say, what to record, and what their rights actually are, we’re changing the game. And in healthcare? We’re holding institutions accountable for neglect, coercion, and bias, especially when it comes to marginalized patients and informed consent.

🛠️ This Is What Justice Tech Looks Like

Justice doesn’t just live in courtrooms. It lives in code, in policy, in everyday choices. Our approach is community-centered, data-informed, and driven by individuals who believe in fundamental care, genuine accountability, and rights that are not compromised behind closed doors.

You don’t need a law degree to stand up for yourself. You need information. You need tools. You need a movement that’s with you, not just watching.

That’s who we are.

🔥 The Future Is Now—And We Need You In It

We’re calling on advocates, donors, healthcare workers, legal professionals, and everyday change-makers to join us. This is bigger than one app or one story. This is about rewriting the rules for how we treat each other and making sure justice finally shows up where it’s needed most.

Let’s build a system where no one’s health or humanity can be weaponized against them.

Because justice by design isn’t just our mission. It’s our blueprint.

In Solidarity,

Ashley T. Martin

CEO, Lustitia Aequalis

Table of Contents:

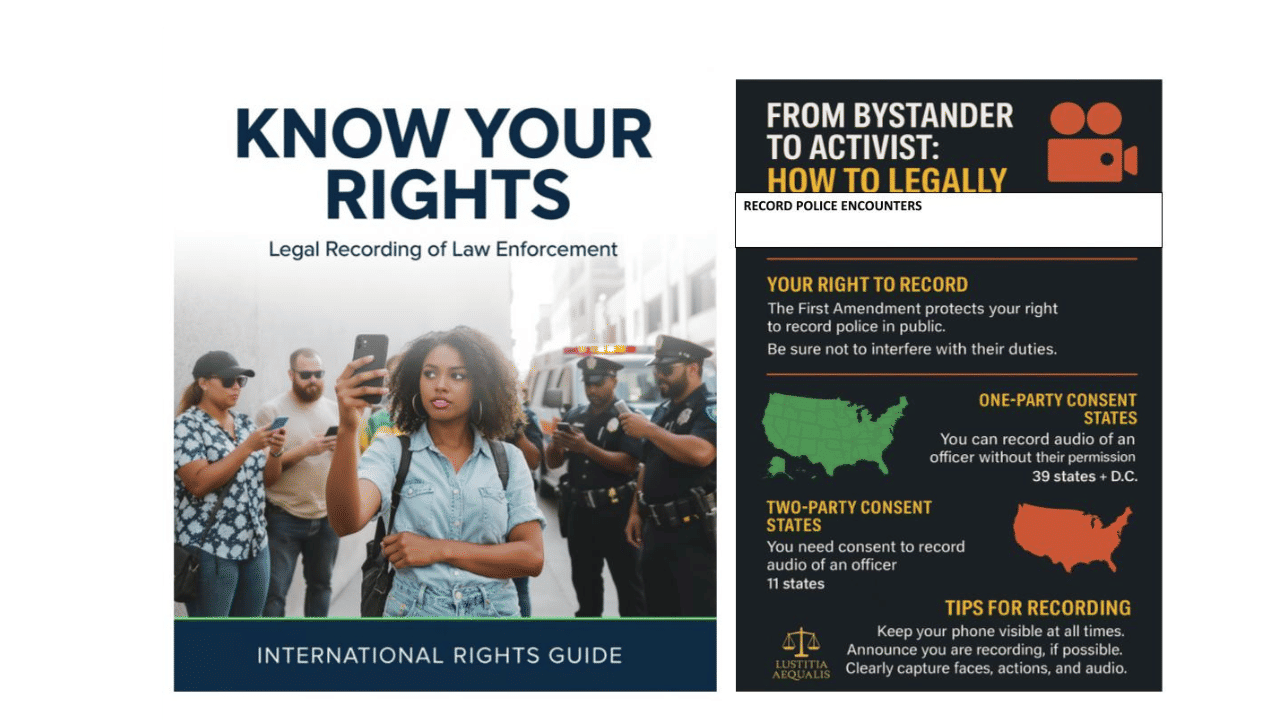

From Bystander to Activist: How to Legally Record Police Encounters

What to Say If You’re Stopped and You’re Undocumented: Real Talk, Real Rights

Can a Hospital Call the Police on You? Know When You’re a Patient, Not a Suspect

The Price of Noncompliance: What Happens When You Say No to a Search?

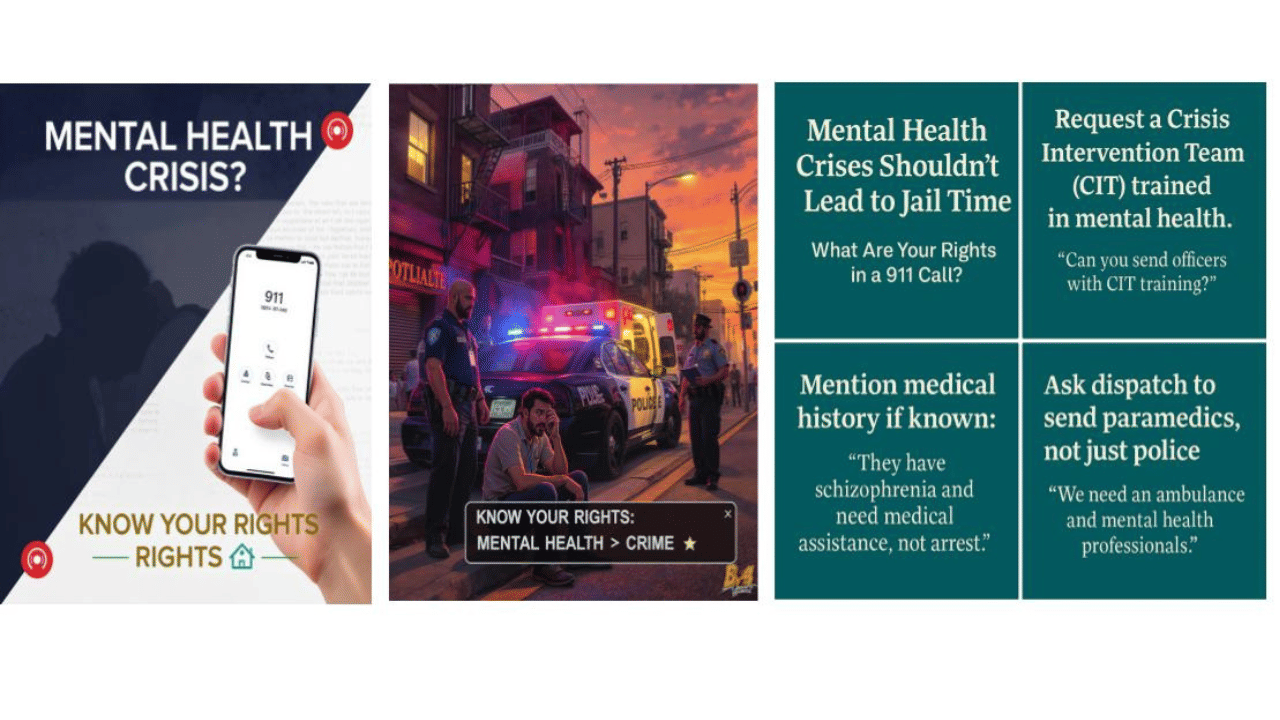

Mental Health Crises Shouldn’t Lead to Jail Time: What Are Your Rights in a 911 Call?

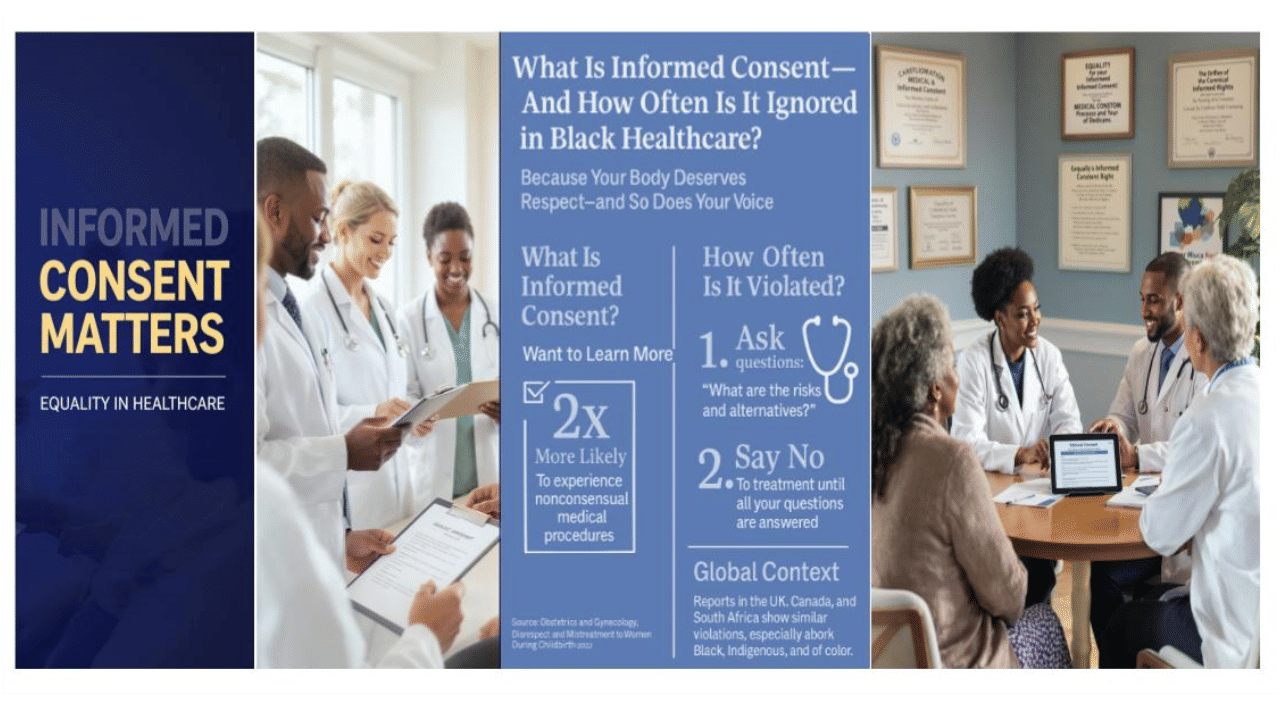

What Is Informed Consent—And How Often Is It Ignored in Black Healthcare?

_(1).jpg)